Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 38

Growing Up With Rockets.

(Original Scan)

Me and my son, just because I can.

These images are in the photo album with all the Pad B pictures, and so these images shall be here, too.

This has nothing to do with Pad 39-B, and I do not care.

This is who we were.

These are the people who grew up with rockets and who worked with rockets.

Kai had a blast growing up here with a father who was into space and space hardware just as much as he was, and he well-appreciates every last bit of it, to this very day.

He knew then, and knows now, just exactly how rare, just exactly how uncanny, every last bit of what we saw together and what we did together, really was and really is. So yeah, we were pretty dialed-in with all of it.

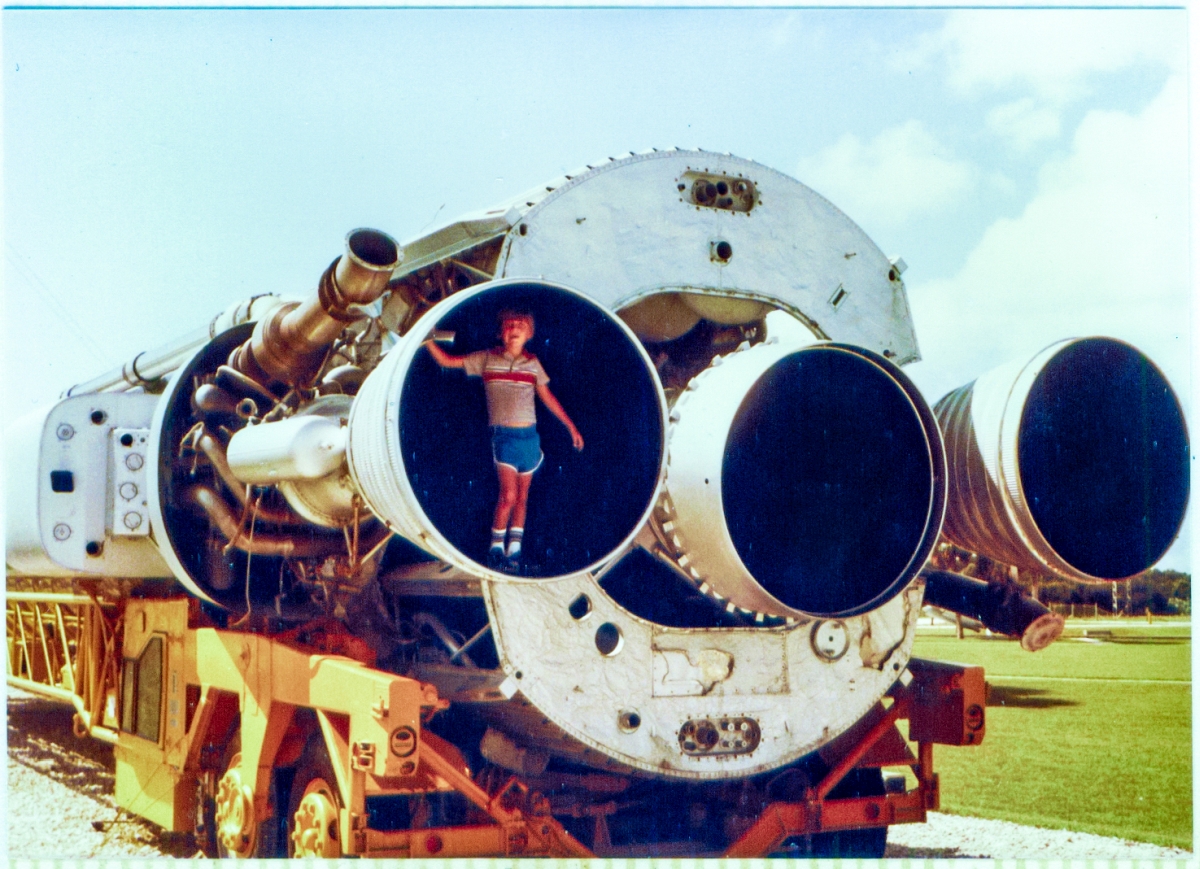

We did this kind of stuff every chance we got, and we got an awful lot of chances. It was an embarrassment of riches and we apologize to no one for any of it. And, by the way, that's a real Atlas that he's standing inside the motor of. Never flew, but it was an honest-to-god piece of flight hardware. Real Stuff.

Lucky kid, huh?

And I was lucky beyond all imagining to have such a human being as Kai to be my own child. To go with. To do with. To be with.

Additional commentary below the image.

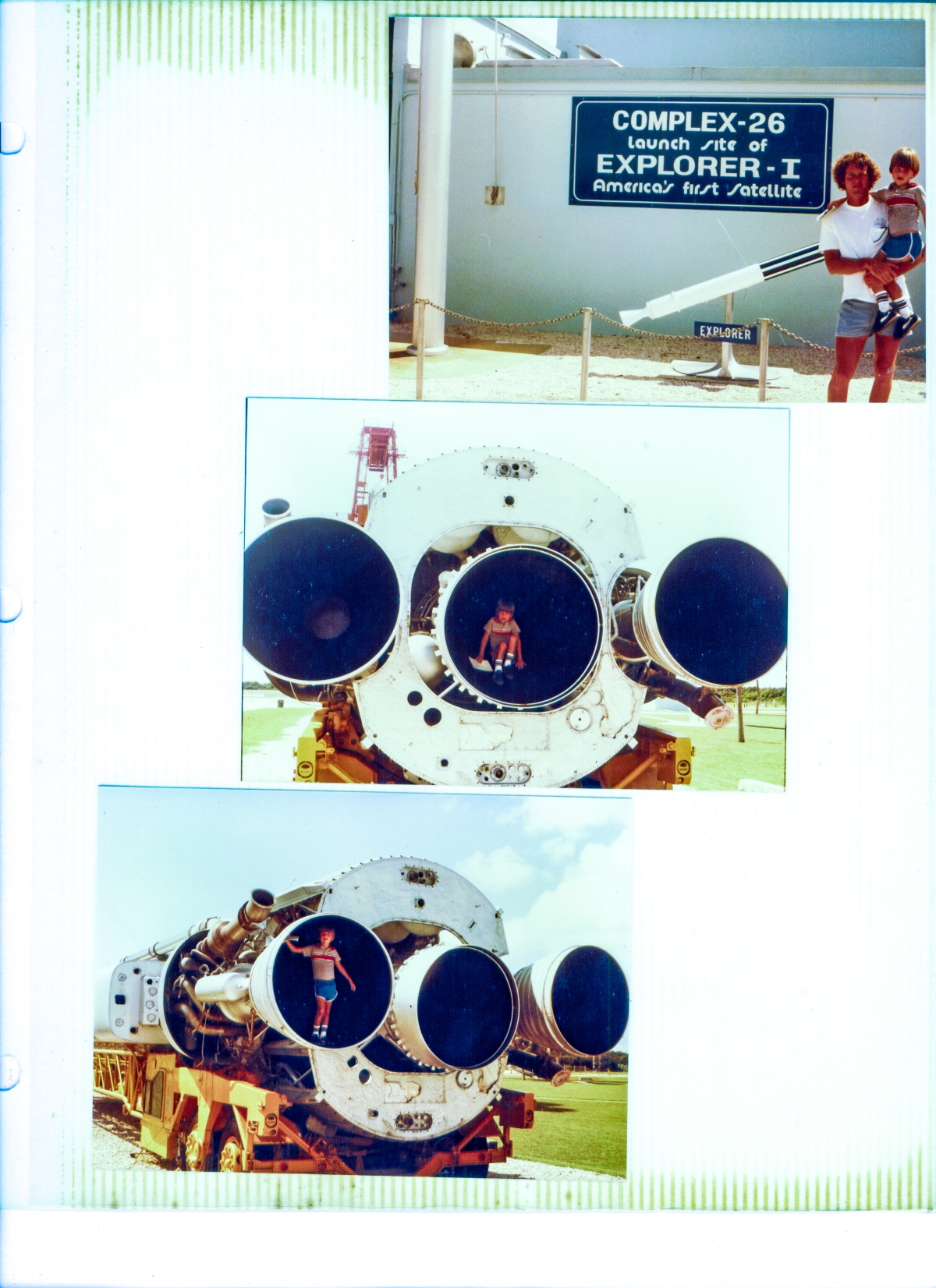

Top: (Reduced)

At the Air Force Space Museum on Cape Canaveral.

Cape Canaveral.

One of those place names that's just dripping in history. A name which is instantly-recognizable, the world around.

A place where impossible things were done. Where people rose above themselves so far that they wound up leaving the Earth.

To this day, the human brain still has trouble with what those people did then, and what those people continue to do today.

And, by my lights, the human brain never will really, properly, come to terms with any of it.

To go to a place where there is no air, no water, no rock, no thing.

To travel at five miles per second,.

Nah. Make that seven miles per motherfucking goddamned second.

Fuck that noise.

There's no way any such kind of thing ever did happen. Ever could happen.

And yet...

And yet there sits the flight hardware.

In mute testimony.

The hardware does not need words.

It is enough, it is more than enough, in and of itself, it is enough that it simply exists.

And so it does, and so it is.

The museum in the form which you see in these images no longer exists. It is no longer a place you can simply drive to without further consideration, preparation, or authorization.

We lived right down State Road A1A from this place, and we would just get in the car and go there.

You can no longer do this.

The museum itself has been moved to a location outside of the restricted areas of Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Launch complexes 26 & 5/6 are no longer accessible to just anybody. You must now arrange with the cognizant authorities for a visit there. You can no longer visit the place alone, on your own, gleefully discover there to be literally not one other person there, and romp with a child who's eyes sparkled in a way that simply cannot be put into words, between the Snark and the LARC, the no-go Navaho and the fat-ass Atlas, the Thor-Able and the Mercury Redstone, the blockhouse and the gantry, the cable trenches and the culverts, the living embodiments of that preternatural marriage of stainless steel and fire which cannot possibly ever have happened.

And yet... it did.

Most of the hardware has been removed, thankfully.

It was a joy beyond describing to have been able to simply walk amongst it, to be able to lay hands upon it, but the air...

The air in Cape Canaveral is a different thing.

The air in Cape Canaveral is a subtle thing.

The air in Cape Canaveral is slow, oh so very slow, but it is relentless and it never stops.

The air in Cape Canaveral is reactive.

The air in Cape Canaveral attacks things. It applies mold to inert surfaces in a way that cannot be recovered from. It bleaches things to pale skeletal shades of death slowly creeping. It takes the finish, takes the shine, completely off of things. It penetrates into the invisible grain of robustly-solid objects and enters waterproof places with a stealth and patience that defies belief. It renders aluminum to a ghastly gray powder. Plastic loses its color, grows brittle, cracks, and eventually falls to pieces under a force no greater than its own weight. Stainless-steel actually rusts. Common steel develops endlessly-growing dark-orange lesions and cankers, exfoliates and dissolves, swells up and sunders heavy concrete emplacements. The air in Cape Canaveral must be experienced to be believed. And it works so slowly. So very very slowly.

You cannot feel it. And there are many who have not spent enough time experiencing it to see what it is truly capable of, how truly destructive it is, and who therefore are unable to believe you when you warn them.

And it was attacking the hardware. The flight hardware sitting defenselessly out beneath a sun that is also a thing that has to be experienced to be believed.

And so they've taken it all away.

They've taken it to a safer place.

And, without sensible budget to do so, they are attempting to restore it.

I can only hope they succeed, because if they do not, there will come a day when all of it is simply gone.

And our thanks for having been given the grace we were given. For having been able to walk amongst it all. While it still existed.

Our thanks knows no bounds, and we are full-aware of just how lucky we were.

We are.

And will remain.

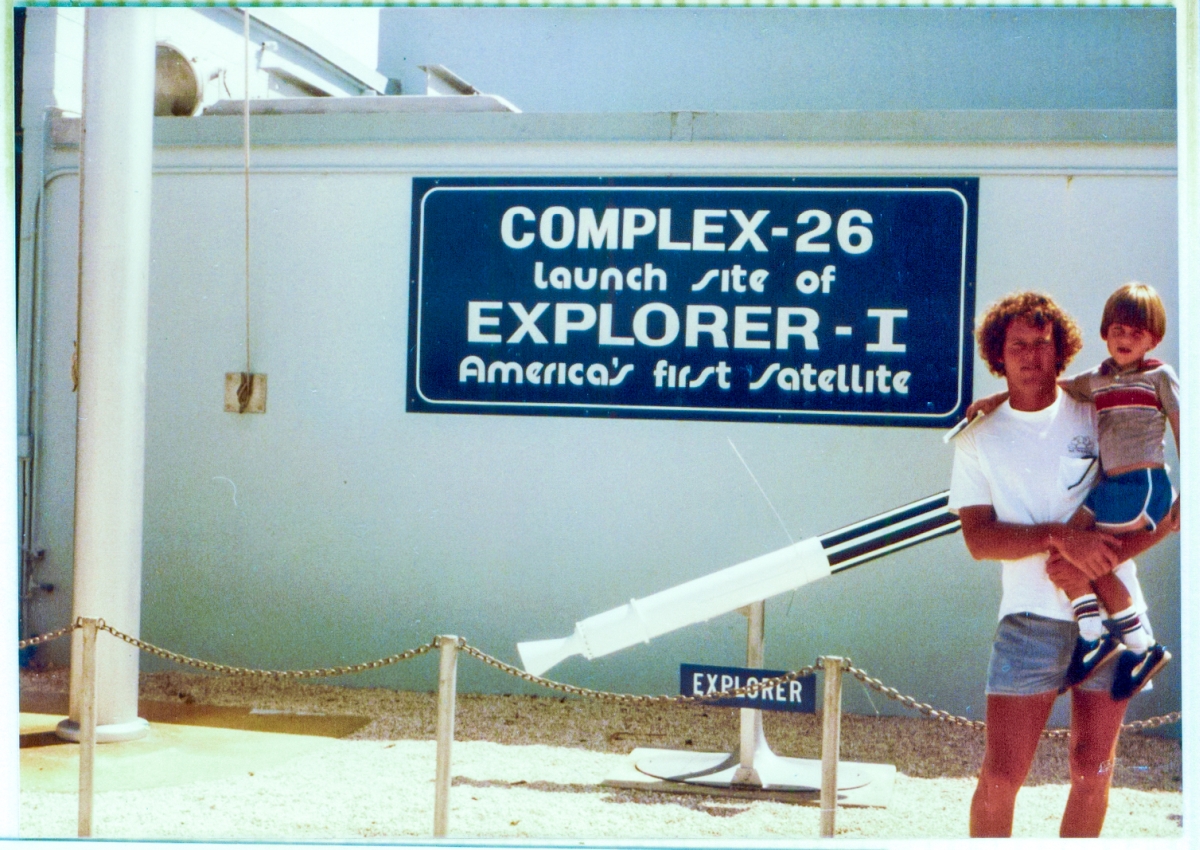

Middle: (Reduced)

This photograph.

How am I even supposed to deal with this photograph?

I cannot. I do not have the strength for this. It is beyond me. Beyond my abilities.

Kai.

I will tell you a story of Kai, instead.

Kai took to this stuff at an astoundingly early age, and showed clear understanding of what was involved, what was going on at an age that I will not even bother to tell you. None of you would believe the least of it.

As a toddler, still working out the details of how to stay above his feet and traverse distances via the use of his legs, he ran afoul of the hot top of a stove.

It was not dire, and it did not leave a mark or scar, but he remembered.

He was from then on, fully checked-out on fire. On heat. On hot objects of any kind. He knew, and that was that.

Ok, fine.

I will tell you that at age three, I was with him in the Salick brother's surf shop on the corner of 3rd Street North and Orlando Avenue in Cocoa Beach, and Rich Salick was in there, and the three of us were considering the airbrushed artwork on the bottom of a surfboard that depicted a Space Shuttle launch in a fair level of detail.

And Rich Salick very accommodatingly inquired of this tiny person, this three-year-old, standing there beside him, well below waist-level, saying with a kindly uncle's smile, "What's that Kai?" while pointing to the air-brushed Space Shuttle on the surfboard.

And the look of flummoxment and stupefaction on his face, a thing rare and sublime, a thing I'll never forget for as long as I live, was profound as he stood there slack-jawed and listened to Kai, in a tiny-child's voice, point to each component in its turn, and with level tones indicate, "That's the Space Shuttle, that's the external tank, and that's the solid rocket boosters."

Perhaps you might have needed to be there to appreciate the fullness of it all, but it's enough to know, that as a very small child indeed, Kai was already up to speed on what rockets were, and what made them go.

Fire made them go, and he knew it with the assurance and aplomb of a seasoned propulsion engineer.

Cut to the Air Force Space Museum.

Same kid. Earlier time. Significantly before these photographs were taken. Can not, will not, divulge an age of this kid, but we're definitely talking about a teeny tiny little Kai.

Kai, me, and his mother are taking him for his first visit to the place, and he was stoked as only a little kid can get stoked about things.

The (small) parking area was in front of, and to the left of, the blockhouse area you see behind me in the image of me holding Kai, above these words.

Place is mostly deserted, maybe one or two other cars in the lot, but it's a large enough area that for all intents and purposes, there's nobody there.

Out of the car.

And right there in front of us, first thing you encounter as you walk on to the property, supported on a pair of stanchions about four feet tall or so, is a Rascal.

Kai knows exactly what it is, and is mightily excited to be in close proximity to it, and eagerly runs toward the rear end of it. The business end of it. The end of it where the motors are.

And as he gets close to it, looks upward from his child's-eye viewpoint and sees those motors from close range, realization sets in and in the twinkling of an eye, he goes from eager, excited, and overjoyed to be there, to a howling mass of wails and tears, and he immediately makes a beeline away from the damn thing at a dead run, back to mom and dad.

And somehow, through some telepathic father-son communications channel that I did not even know we possessed, I almost as quickly knew.

I knew what was upsetting him so much.

I knew that in his little-kid's mind, he had not yet reached the point of being able to distinguish between a piece of flight hardware on outdoor display in a museum, and a real, live, missile.

He had already been fully checked out on fire, and he harbored no doubts whatsoever that fire was what came out of those awful nozzles at the back of that thing, and he wanted nothing to do with any of it.

I scooped him up in my arms and told him it was going to be ok, that the rocket was not going to spit a torrent of fire and burn him, but it was to no avail.

Our happy trip to the museum was over before it had even begun, and perplexment was upon me as I tried to figure out what to do next.

And then, once again through some sort of telepathy, I suddenly had the answer, and once again I knew, without knowing how I knew, and I took prompt action without cracking my brain any further over things.

The Rascal was not the only missile on display.

Not by a long shot.

Atlas, Titan, Snark, Redstone, Thor-Able, Bull Goose, World War II German V-1, and plenty more. Lots and lots and lots of terrifying missiles and all of them complete with motors and nozzles that would spit enough fire to put hell to shame.

From Kai's point of view, we were quite likely in the Worst Place in the World.

And more or less right in the middle of all of it, sitting on a flat concrete expanse, the Thor-Able stood high above its surroundings, on a stand that left the bottom edge of its quite-large rocket nozzle

mere inches above the concrete. Maybe a full foot, maybe not. And it was unfenced and completely exposed to the elements and the people who might pay this place a visit.

And so I continued to hold Kai in my arms, and against his strident protests, and not allowing him to escape, I marched off past the Rascal and out into the heart of things.

Kai had no doubt whatsoever that I had lost my mind and we were all going to die, and he was not shy in the slightest about letting me know this with a flurry of howls, wails, and escape attempts, but despite it all, I soldiered on until we came to that dreadfully large nozzle at the bottom of the Thor-Able.

Kai was one unhappy little kid. Very very unhappy.

His fit had not subsided in the slightest when I firmly took his wrist in my right hand, and from about a foot away, forcibly placed his unwilling hand directly upon the metal of that horrifying nozzle and kept it there.

And all of a sudden, everything changed.

Despite a continued onslaught of wails and tears, Kai had been keeping his eye on things, and had not lost his awareness of his surroundings.

And as his hand continued to rest upon the cool metal of the nozzle, further realization set in, and all of a sudden he knew that no fire was going to be coming out of this, or any other missile in the field which we were standing in the middle of.

And the tears went away instantly, and the howls and wails went away instantly, and the squirms and wiggles were altered in a way that told me to put him down and let go of him.

Which I did.

And he took off like he himself was a rocket.

A tiny guided missile flying just above the grass and concrete from first one rocket on display, to another, and another, and another.

To see them all.

To touch them all.

And his joy, and my joy, knew no bounds that day.

And now perhaps, you can look at the image above these words once again, and understand why I do not have the strength to deal with it.

Kai is very happily sitting deep inside the nozzle of the sustainer engine on this Atlas rocket. A piece of flight hardware. And he knows exactly what it is.

And he is very happy indeed to be here after I lifted him up, placed him inside of it, and backed away with my camera far enough to get this frame.

Let Croesus have his riches.

Let the famous have their fame, let the powerful have their power.

I have something vastly greater, and I am both humbled and stupefied that a thing as great as this could have fallen to me.

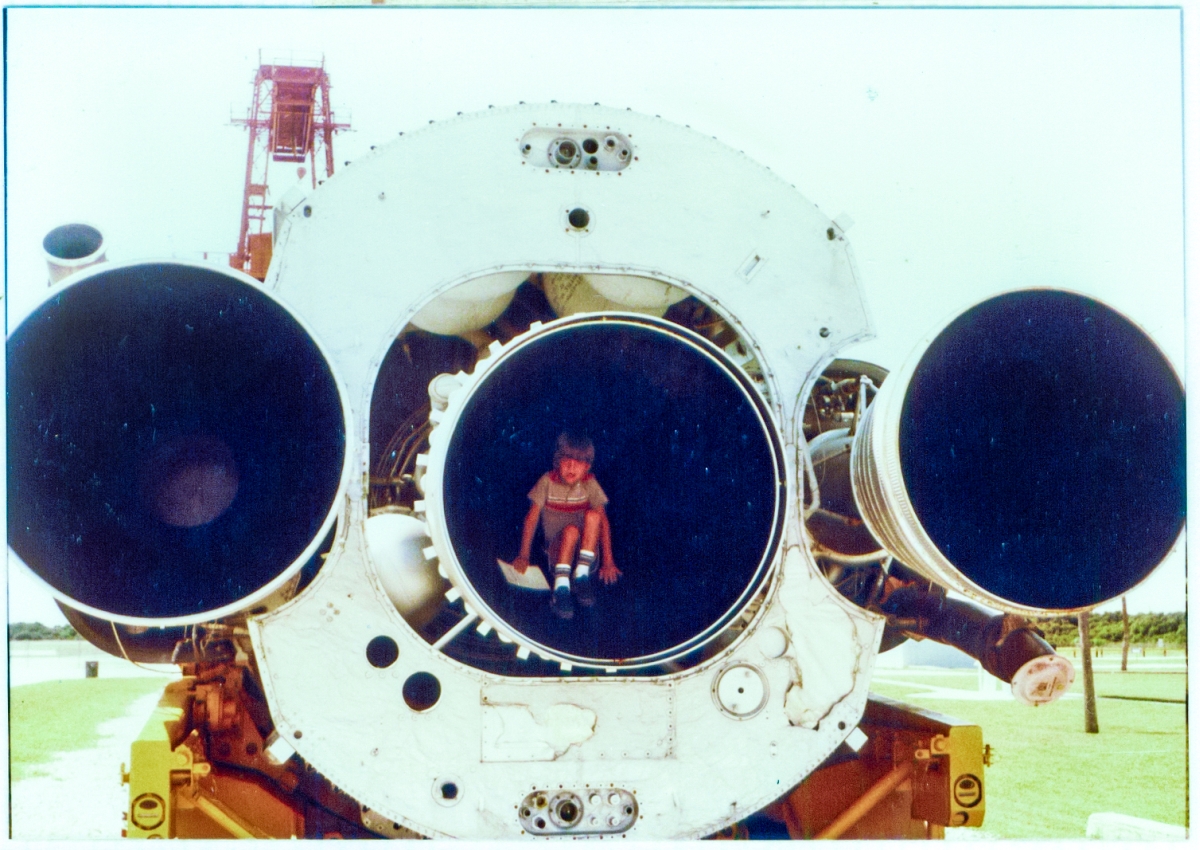

And on a day as glorious as this, of course we shall move from the sustainer engine to one of the booster engines.

How could we not?

Kai contines to happily clutch the flier they hand out (the contents of which, by this time, he was possibly more knowledgeable about than the people who wrote the damn thing) when you come to this place.

In this frame, you can see that they have very kindly removed some of the covering which ordinarily shrouds the entire engine compartment of the Atlas, and we spent no end of time examining, marveling at, and just generally admiring things in there.

You cannot see it in this image, but some of the welds in the piping in there were just beyond belief. Uncannily beautiful and symmetric. Master Craftsman stuff.

Beneath it all, painted in the ubiquitous shade of bright yellow which was commonplace for all such similar equipment back in those days, the stretcher bears its load.

Look closely in the bottom left corner of this image and you'll see, just forward of the wheels, a very small cab, complete with a side window.

Perhaps later on, we'll get a bit further into the particulars of this small cab.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |